Have you ever typed something simple into ChatGPT like “Can you, please, explain this term?” or “What should I cook for dinner?”, and hit “Enter” without a second thought? Most of us do it dozens of times per week. Sometimes out of curiosity. Sometimes out of boredom. Sometimes simply because AI has become something… well, casual. But here’s the problem: behind that friendly chat window lies an enormous chain of servers, data centres, cooling systems, and power grids that light up every time you send a message. The action feels weightless, but it isn’t. Not even close.

And the more AI becomes part of our everyday life, the more important it is to understand what’s happening behind the scenes. While AI offers powerful tools for optimizing systems and potentially solving sustainability problems, its own development and deployment come at a substantial environmental cost.

What happens when you send a prompt

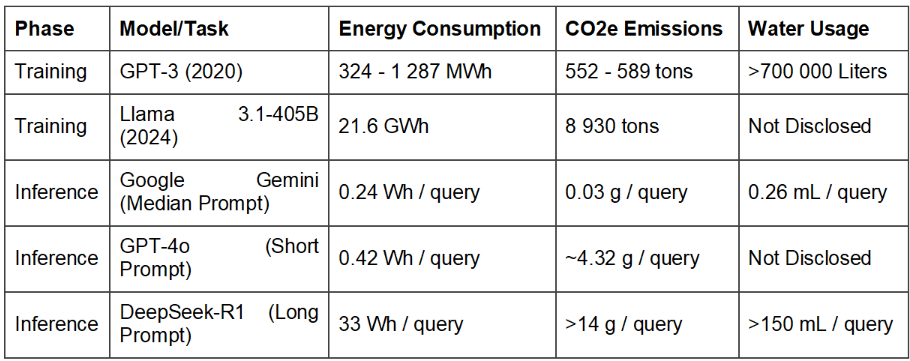

AI has many different effects on the environment. It is distributed across two primary phases: training and inference. While training a frontier model requires a significant one-time energy investment, the cumulative cost of inference, or running the model for billions of daily user queries, is widely recognized as the primary long-term driver of AI’s environmental footprint. This shift in perspective is crucial for ESG accounting as it reframes AI’s impact from a one-off capital cost to a continuous, operational one.

Effect of different models on ecology

And, yes, that small, casual question like “Do you know a good pasta recipe?” may consume energy comparable to around 5 minutes of smartphone charging (assuming a charging phone consumes 5 Wh).

A single training run for a model like Llama 3.1 emits as much CO2 as thousands of round-trip flights, but the daily inference footprint of a platform like ChatGPT, with over 2 billion daily queries, quickly eclipses this one-time cost. A scaled-up scenario for GPT-4o, assuming 772 billion queries annually, projects an annual energy consumption between 391 509 and 463 269 MWh – an amount surpassing the annual electricity use of 35 000 U.S. homes. This demonstrates that as AI services become ubiquitous, their operational footprint becomes the primary concern.

Beyond electricity, AI’s thirst for water represents a significant and often underreported environmental liability. Data centres require vast amounts of freshwater for cooling the powerful servers that run AI workloads, and this demand is creating pressure on local water resources, especially in arid regions. The amount of water used is astonishing. Training GPT-3 alone utilized more than 700 000 liters of on-site freshwater, which rises to 5.4 million litres when the water used to generate the requisite electricity is included (Scope 2). Total AI-related water withdrawals are expected to reach 4.2 to 6.6 billion cubic meters per year by 2027, accounting for more than half of the United Kingdom’s annual freshwater demand. Even a modest user activity, such as asking 20-50 questions of ChatGPT, can consume approximately 500 ml of water.

But the real problem – our unawareness of these costs

Most people don’t realise what stands behind a single prompt. Not because we’re careless, but because no platform shows any energy indicators. You don’t see: “This joke you asked for used 0.42 Wh of electricity.” These “prompt explosion” is a product of UI design:

● AI chatbots encourage continuous chatting.

● Tools autocomplete, suggest, rephrase, rewrite endlessly.

● Many interactions replace tasks that already had efficient alternatives.

One of the most effective strategies for reducing AI’s environmental footprint is to match the model to the task. It is extremely inefficient to use a large, general-purpose Large Language Model (LLM) for straightforward, repetitive activities. These tasks can be completed with similar precision by smaller, specialized models (SLMs) using a fraction of the energy. A significant portion of AI’s inference footprint comes from the accumulation of “trivial” or low-value queries, such as casual greetings or simple requests better suited for a search engine. Studies suggest that implementing user experience (UX) nudges, rate limits, or quotas could reduce these queries by 5-20%. A 10% reduction in ChatGPT’s daily queries could save enough electricity to power 3 500 U.S. homes for a year.

Smarter routing can be implemented inside of the AI models. Not every prompt needs a giant model, lightweight ones can answer ~60% of queries. And a simple decision matrix can guide developers toward more sustainable choices:

● Is the task highly specific and repetitive (e.g., translation, summarization, sentiment analysis)? → Default to a pre-trained, fine-tuned SLM.

● Is the task complex, requiring multi-step reasoning, creativity, or broad world knowledge? → Consider an LLM, but start with the smallest viable version (e.g., a 7B or 13B parameter model) before scaling up.

● Is latency or on-device deployment critical? → An SLM is almost always the better choice due to its smaller size and faster inference time.

For routine tasks, SLMs are not just a viable alternative. They are the sustainable default. Organizations can achieve massive energy savings by implementing a decision framework that defaults to the smallest effective model for a given job.

Climate-positive AI applications

While AI’s own footprint is a major concern, it also possesses the unique potential to solve complex environmental problems and generate a net-positive impact. When targeted correctly, AI can optimize systems to reduce energy consumption, minimize waste, and improve climate resilience, often with a return on its own carbon investment measured in days or weeks.

● Google DeepMind helped reduce cooling energy in some data centres by up to 40%.

● AI-based forecasting improves renewable-energy integration.

● Precision agriculture systems powered by AI reduce fertiliser use and water waste.

● AI optimises supply chains, reducing fuel consumption in logistics.

In many scenarios, the emissions AI helps avoid can exceed the emissions required to run it if used correctly.

So, AI isn’t a villain. It’s a resource that consumes more energy than most people expect, but also one that can actively reduce emissions in high-impact industries. As Paracelsus once said, “Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison”. AI is a powerful tool that should be used wisely, thoughtfully designed, and with reasonable expectations. The real challenge is not individual queries. It’s the collective shift towards millions of small, unnecessary interactions. One pointless prompt is insignificant. But billions of them? That’s a trend which already makes a real impact. And to change it we need to design new systems and habits recognising our own footprint and making more conscious decisions.

And the sooner we bring this to the public, the more responsibly we can build the next generation of technologies that benefit both people and the environment.